26 February 2018

Author: Richard Jerram, Chief Economist, Bank of Singapore, Member of OCBC Wealth Panel

The US government bond market is facing a surge in supply over the coming couple of years. This will increase upwards pressure on yields, which could add to the strain on risk assets.

IMF Chief Christine Lagarde often urges policy-makers to “fix the roof while the sun is shining”. To pursue this analogy, US officials are sitting around the pool with a beer, enjoying a barbeque. Rather than taking advantage of strong economic conditions to repair public finances, they are imprudently sending US borrowing even higher.

There are no immediate perils in this approach – other than pushing up bond yields – but it will limit the room for manoeuvre when the next recession strikes, especially as the potential to cut interest rates is likely to be less than usual. The short-term impact on growth from the tax cuts and increased spending that is behind the higher borrowing will be positive, but there is no need for fiscal stimulus when the economy is already at full employment.

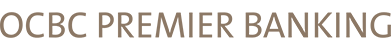

Normally, US government borrowing goes up and down with the unemployment rate. This makes sense – when the economy is doing badly, government tax revenues struggle and some parts of spending rise, so the deficit increases.

The past two years are unusual with the unemployment rate falling, but the budget deficit rising. That will continue in 2018-19 as a result of the recent tax reform and deal to lift the debt ceiling. The deficit is already well over 3% of GDP and is set to rise above 5% by 2019.

The past two years are unusual with the unemployment rate falling, but the budget deficit rising. That will continue in 2018-19 as a result of the recent tax reform and deal to lift the debt ceiling. The deficit is already well over 3% of GDP and is set to rise above 5% by 2019.

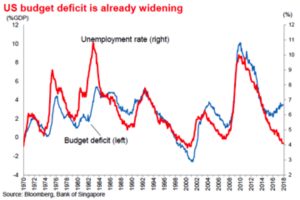

This is a big contrast with the lengthy expansion of the 1990s when the US was running a budget surplus and paying down government debt. Most previous periods of growth had seen debt track sideways or down.

Government debt inevitably spiked higher after the 2008-09 financial crisis and recession, but eight years of recovery have seen no progress in bringing it down. Now it is set to head even higher. A rule of thumb for developed economies is that it is prudent to hold the budget deficit below 3% of GDP with debt below 60%, and the US is well beyond both measures.

Government debt inevitably spiked higher after the 2008-09 financial crisis and recession, but eight years of recovery have seen no progress in bringing it down. Now it is set to head even higher. A rule of thumb for developed economies is that it is prudent to hold the budget deficit below 3% of GDP with debt below 60%, and the US is well beyond both measures.

At least the recent $1.5tr infrastructure plan is unlikely to add to government debt, for the simple reason that it is not going to happen. Repairing ageing infrastructure would probably bring more lasting benefit to the economy than tax cuts, but it has little support in Congress.

Remember that the Federal Reserve is also adding supply into the bond market as it reverses its quantitative easing programme. By the end of this year the Fed’s holdings of US government debt will be falling at an annual rate of $360bn (2% of GDP).

This is all a headwind for US Treasury yields, but not a catastrophe. Empirical studies suggest that the Fed’s balance sheet reduction could add about 10bps per year to yields, while the deficit increase puts on another 20-30bps. Markets are forward looking, so some of this will already have happened and (at least partly) explains the rise in yields over the past couple of months.

There are several other related risks. The most obvious is that pushing a big fiscal stimulus into a mature cyclical recovery will add to the risk of overheating and force the Fed to be more aggressive. We are looking for four rate hikes this year, with more to come in 2019. Allied to this is the upwards pressure on bond yields as supply increases. This could be compounded by reduced demand from overseas as monetary tightening spreads across most developed economies. This adds up to a tightening of monetary conditions that could become a meaningful drag on growth before the end of next year.

The next risk is that the higher budget deficit sparks a political reaction that leads to pressure to cut spending. “Starve the beast” is a Republican Party strategy involving cutting taxes in order to reduce the amount of funding available for welfare. If government support for low income groups is cut in 2019-20 then there will be an immediate impact on consumer spending (as this group tends to have little or no savings to fall back on). This could come just as Fed rate hikes are starting to bite and risk sending the economy into recession.

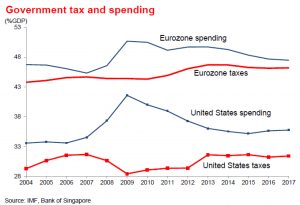

In fact, compared to European economies the US stands out for having a low tax take, rather than high government spending.

In fact, compared to European economies the US stands out for having a low tax take, rather than high government spending.

The final risk is that future policy flexibility will be constrained by failing to “fix the roof while the sun is shining”. The 2001 recession began when the budget was in surplus (2.4% of GDP) and debt was 55% of GDP. The 2008 recession started with a deficit of 1.5% of GDP and debt of 64%. Heading into recession with a deficit of 5% of GDP and debt over 100% does not leave a lot of room for manoeuvre. Moreover, in a low growth, low inflation world, the room to cut interest rates is likely to be less than in previous downturns.

Burgeoning supply is not the only problem facing the US bond market. Rising inflation is a normal feature of a mature economic cycle and we can expect a continued pick-up over the coming year.

Most of these factors should be relatively slow-moving, but we expect continued upwards pressure on yields. We see 10-year Treasuries yielding 3.25% in a year’s time, and this also supports our underweight position in investment grade bonds.

We can also think back to the 1980s when Reagan’s tax cuts led to a big budget deficit, which in turn contributed to a current account deficit. These “twin deficits” were seen as a force behind the weak exchange rate. In fact there is not a hard connection between the two deficits, and also no consistent link between twin deficits and a falling exchange rate, but there is a risk that financial markets see merit in the narrative and take it as a reason to sell USD.

Important Information

This material is not intended to constitute research analysis or recommendation and should not be treated as such.

Any opinions or views expressed in this material are those of the author and third parties identified, and not those of OCBC Bank (Malaysia) Berhad (“OCBC Bank”, which expression shall include OCBC Bank’s related companies or affiliates). OCBC Bank does not verify or endorse any of the opinions or views expressed in this material. You should beware that all opinions and views expressed are subject to change without notice, and OCBC Bank does not undertake the responsibility to update anyone with any changes to the opinions and views expressed.

The information provided herein is intended for general circulation and/or discussion purposes only and does not contain a complete analysis of every material fact. It does not take into account the specific investment objectives, financial situation or particular needs of any particular person. Without prejudice to the generality of the foregoing, please seek advice from a financial adviser regarding the suitability of any investment product taking into account your specific investment objectives, financial situation or particular needs before you make a commitment to purchase the investment product. In the event that you choose not to seek advice from a financial adviser, you should consider whether the product in question is suitable for you.

OCBC Bank is not acting as your adviser. This material is provided based on OCBC Bank’s understanding that (1) you have sufficient knowledge, experience and access to professional advice to make your own evaluation of the merits and risks of any investment product and (2) you are not relying on OCBC Bank or any of its representatives or affiliates for information, advice or recommendations of any sort except for specific factual information about the terms of the transaction proposed. This does not identify all the risks or material considerations that may be associated with any of the investment products. Prior to purchasing the investment product, you should independently consider and determine, without reliance upon OCBC Bank or its representatives or affiliates, the economic risks and merits, as well as the legal, tax and accounting characterisations and consequences of the investment product and that you are able to assume these risks.